- EN

- FR

- ES

Open letter to signatories to the Convention on Biological Diversity on the 30x30 target

An urgent call to recognise and respect the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities ahead of COP15

Dear National Delegations,

The biodiversity crisis is among the gravest threats facing humanity. When you gather in Kunming this year for the UN Biodiversity Conference, you will have one of the last and best opportunities to stop the destruction of the world’s lands and oceans and put them on a pathway to sustainability.

As you finalise your rescue plan for nature – the Post 2020 Global Biodiversity Framework – we fishers and farmers, we conservationists and environmentalists, we human rights advocates and scientists urge you to live up to your responsibilities for people and planet and fully recognise that the best way to protect nature is to protect the human rights of those who live among it and depend upon it.

Nature is vital for all of us. It drives climate and weather, supplies oxygen and food, stores carbon and heat and supports culture and well-being. These benefits should be enjoyed by everyone, but this is sadly not the case.

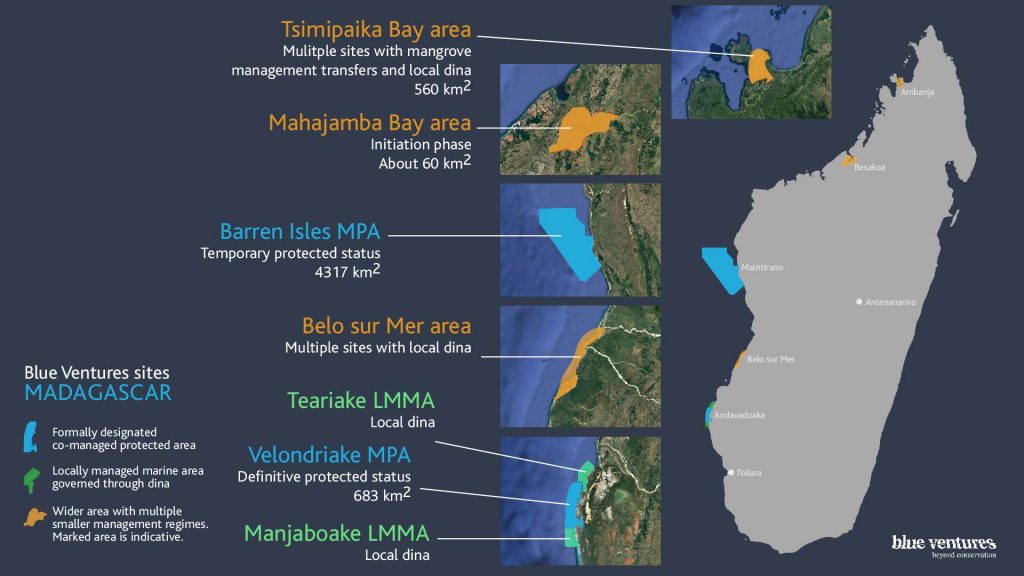

To take just two examples from many, the hundreds of millions of men and women involved in small-scale fisheries form the largest group of ocean users on the planet. They are the primary rights holders to whom the ocean economy must be accountable, yet, around the world coastal communities have been marginalised by large corporate interests and excluded from the policy discourse. Because of this power imbalance, they bear the costs and are wrongly blamed for the environmental degradation caused by industrial fishing fleets. All too often, they’re denied access to their fishing grounds in the name of coastal development, conservation or fisheries management. All too often, they’re powerless to prevent those same grounds from being devastated by industrial vessels.

Indigenous Peoples and local communities have often proven to be better stewards of land than governments, with at least 42% of all global land in good ecological condition under the stewardship of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. There is also growing evidence of the effectiveness and equitability of locally-led approaches to ocean conservation. Yet, over the last century, millions have been forced from their lands in the name of conservation, often violently: the “no people allowed” baggage of traditional fortress conservation has proven difficult to shed. For many Indigenous peoples and local communities, conservation remains an exclusionary practice – one that pits people against nature.

A principal component of your new plan to save nature is target 3, which calls for the protection of at least 30% of global land and ocean by 2030. This target, often referred to as 30×30, represents a commitment to halt biodiversity loss and transform humanity’s relationship with nature. But decades of learning from the field of conservation shows that it will fail unless it emphasises the primacy of human rights and recognises the centrality of Indigenous peoples and local communities to conservation success.

We call on the leaders of every country and their representatives at COP15 to avert the impending biodiversity catastrophe by ensuring that 30×30 commitment is implemented with the free, prior and informed consent, participation and leadership of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

Specifically:

- We call on you to do more for people and the planet, by recognising that conservation and environmental management strategies need to go beyond 30% and support a 100% management approach, addressing the underlying drivers of resource degradation and biodiversity loss that also affect the other 70%.

- We call on you to secure and explicitly reference the rights and tenure of small-scale fishers, smallholder farmers and Indigenous Peoples and local communities, in Target 3 through the “recognition and protection of Indigenous Peoples’, local communities’ and traditional resource users’ title, tenure, access, and resource rights to land and ocean and prioritises locally-led or collaborative governance and management systems”

- We call on you to recognise that free, prior and informed consent means respecting the rights of communities and Indigenous peoples to not participate in the 30×30 process and not have their territories designated as conservation measures or protected areas.

- We call on you to drastically increase direct financial support to Indigenous Peoples and local communities in pursuit of conservation, recognising that despite their hugely valuable contributions to conservation and environmental management, they receive only a fraction of the available finance.

These actions will go a long way towards ensuring that 30×30 is more than just aspiration. We urge you, our leaders, to adopt and implement them without delay. Coexistence between people and nature is entirely possible, but can only be achieved at scale with the full engagement of those who depend most on nature: those historically marginalised people who have contributed the least to the biodiversity crisis. This strategy is key to securing a future for all life on earth.

Yours faithfully,

Lettre ouverte aux signataires de la Convention sur la diversité biologique concernant l'objectif 30x30

Un appel urgent à reconnaître et à respecter les droits des peuples autochtones et des communautés locales avant la COP15

Chères délégations nationales,

La crise de la biodiversité est l’une des menaces les plus graves auxquelles l’humanité doit faire face. Lorsque vous vous réunirez à Kunming cette année pour la conférence des Nations Unies sur la biodiversité, ce sera pour vous l’une des dernières et des meilleures chances de mettre un terme à la destruction des terres et des océans de la planète.

Alors que vous finalisez votre plan de sauvetage de la nature – le Cadre mondial de la biodiversité pour l’après-2020 – nous, pêcheurs et agriculteurs, défenseurs de l’environnement et de la nature, défenseurs des droits humains et personnalités scientifiques, vous demandons d’assumer vos responsabilités envers les personnes et la planète et de reconnaître pleinement que la meilleure façon de protéger la nature est de protéger les droits humains de celles et ceux qui vivent en interaction avec elle et qui en dépendent.

La biodiversité est vitale pour nous tous. Elle détermine le climat et le temps, fournit de l’oxygène et de la nourriture, stocke le carbone et la chaleur et favorise la culture et le bien-être. Chacun de nous devrait pouvoir profiter de ces avantages, mais ce n’est malheureusement pas le cas.

Pour ne prendre que deux exemples parmi tant d’autres, les centaines de millions d’hommes et de femmes impliqués dans la pêche traditionnelle forment le plus grand groupe d’utilisateurs des océans de la planète. Ils sont les principaux détenteurs de droits humains auxquels l’économie des océans doit rendre des comptes. Pourtant, partout dans le monde, les communautés côtières ont été marginalisées par les grandes entreprises et exclues des discours politiques. En raison de ce rapport de forces inéquitable, ces communautés supportent les coûts et sont accusées à tort de la dégradation de l’environnement causée par les flottes de pêche industrielle. Trop souvent, on leur refuse l’accès à leurs zones de pêche au nom du développement côtier, de la protection de l’environnement ou de la gestion des pêches. Trop souvent, ces communautés sont impuissantes à empêcher que ces mêmes zones soient dévastées par les navires industriels.

Les peuples indigènes et les communautés locales se sont souvent révélés être de meilleurs gestionnaires des terres que les gouvernements. Au moins 42 % des terres mondiales en bon état écologique sont gérées par des peuples indigènes et des communautés locales. Il existe également de plus en plus de preuves de l’efficacité et de l’équité des approches locales de la gestion durable des océans. Pourtant, au cours du siècle dernier, des millions de personnes ont été chassées de leurs terres au nom de la protection de l’environnement, souvent de manière violente : il est difficile de se débarrasser de l’approche historique selon laquelle il faudrait ériger des forteresses pour protéger la nature contre les personnes. Pour de nombreux peuples indigènes et communautés locales, la conservation reste une pratique d’exclusion, qui oppose les gens à la nature.

L’un des principaux éléments de votre nouveau plan de sauvegarde de la nature est la cible 3, qui appelle à la protection d’au moins 30 % des terres et des océans de la planète d’ici à 2030. Cette cible, souvent appelée “30×30”, représente un engagement à mettre un terme à la perte de biodiversité et à transformer la relation de l’humanité avec la nature. Mais des décennies d’apprentissage dans le domaine de la protection de l’environnement montrent que cet objectif est voué à l’échec s’il ne met pas l’accent sur la primauté des humains et ne reconnaît pas le rôle central des peuples autochtones et des communautés locales dans la réussite de la protection durable de l’environnement.

Nous appelons les dirigeants de tous les pays et leurs représentants à la COP15 à éviter une catastrophe irréversible en termes de biodiversité en s’assurant que l’engagement 30×30 est mis en œuvre avec le consentement préalable et éclairé, la participation et le leadership des peuples autochtones et des communautés locales.

Plus précisément :

- Nous vous demandons de faire plus pour les peuples et la planète, en reconnaissant que les stratégies de protection et de gestion durable de l’environnement doivent aller au-delà des 30 % et soutenir une approche de gestion durable pour 100 % des terres et océans, en s’attaquant aux moteurs sous-jacents de la dégradation des ressources et de la perte de biodiversité qui affectent également les 70 % restant.

- Nous vous demandons de garantir et de mentionner explicitement les droits humains et les droits en matière de propriété des pêcheurs artisanaux, des petits exploitants agricoles, des peuples autochtones et des communautés locales, dans la cible 3, en “reconnaissant et en protégeant les droits de propriété, d’occupation, d’accès et d’utilisation des ressources des peuples autochtones, des communautés locales et des utilisateurs traditionnels des terres et des océans, et en donnant la priorité aux systèmes de gouvernance et de gestion menés localement ou en collaboration”.

- Nous vous demandons de reconnaître que le consentement libre, préalable et éclairé implique de respecter les droits des communautés et des peuples autochtones à ne pas participer au processus 30×30 et à ne pas voir leurs territoires désignés comme soumis à des mesures externes de protection ou comme zones protégées.

- Nous vous demandons d’augmenter de manière drastique le soutien financier direct aux peuples autochtones et aux communautés locales dans la poursuite de la gestion durable de l’environnement, en reconnaissant que malgré leurs contributions extrêmement précieuses à la protection et à la gestion de l’environnement, ils ne reçoivent qu’une fraction des financements disponibles.

Ces actions contribueront grandement à faire en sorte que 30×30 soit plus qu’une simple aspiration. Nous vous exhortons, vous, nos dirigeants, à les adopter et à les mettre en œuvre sans délai. L’harmonie entre l’humanité et la nature est tout à fait possible, mais ne peut être réalisée à grande échelle qu’avec l’engagement total de celles et ceux qui dépendent le plus de la nature : les personnes historiquement marginalisées qui ont le moins contribué à la crise de la biodiversité. Cette stratégie est essentielle pour garantir un avenir à toute vie sur terre.

Je vous prie d’agréer, Madame, Monsieur, l’expression de mes sentiments distingués.

Carta abierta a los signatarios del Convenio sobre la Diversidad Biológica sobre el objetivo 30x30

Un llamamiento urgente para que se reconozcan y respeten los derechos de los pueblos indígenas y las comunidades locales antes de la COP15

Estimadas delegaciones nacionales,

La crisis de la biodiversidad es una de las amenazas más graves a las que se enfrenta la humanidad. Cuando ustedes se reúnan en Kunming este año para la Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre la Biodiversidad, tendrán una de las últimas y mejores oportunidades para detener la destrucción de las tierras y los océanos del mundo y procurar un futuro más sostenible para éstos.

Mientras ustedes finalizan su plan de rescate de la naturaleza -el Marco Global de Biodiversidad Post 2020- nosotros, pescadores y agricultores, nosotros, conservacionistas y ecologistas, nosotros, científicos y defensores de los derechos humanos, les instamos a estar a la altura de sus responsabilidades para con las personas y el planeta y a reconocer plenamente que la mejor manera de proteger la naturaleza es proteger los derechos humanos de quienes viven y dependen de ella.

La naturaleza es vital para todos nosotros. Impulsa el clima y el tiempo meteorológico, suministra oxígeno y alimentos, almacena el carbono y el calor, y apoya la cultura y el bienestar. Estos beneficios deberían ser disfrutados por todos, pero lamentablemente no es así.

Por poner sólo dos ejemplos entre muchos, los cientos de millones de hombres y mujeres que se dedican a la pesca a pequeña escala, constituyen el mayor grupo de consumidores de los océanos del planeta. Son los principales titulares de derechos ante los que la economía de los océanos debe rendir cuentas, pero en todo el mundo las comunidades costeras han sido marginadas por los grandes intereses empresariales y excluidas del discurso político. Debido a este desequilibrio de poder, sufren las consecuencias y se les culpa erróneamente de la degradación medioambiental causada por las flotas pesqueras industriales. Con demasiada frecuencia, se les niega el acceso a sus caladeros en nombre del desarrollo costero, la conservación o la gestión de la pesca. Y con demasiada frecuencia, se ven impotentes para evitar que esos mismos caladeros sean devastados por buques industriales.

Los pueblos indígenas y las comunidades locales han demostrado a menudo ser mejores administradores de la tierra que sus propios gobiernos, consiguiendo que al menos un 42% de toda la tierra a nivel mundial esté en buen estado ecológico. También hay cada vez más pruebas de la eficacia y la equidad de los enfoques locales para la conservación de los océanos. Sin embargo, a lo largo del último siglo, millones de personas se han visto obligadas a abandonar sus tierras en nombre de la conservación, a menudo de forma violenta: el bagaje de “no se admiten personas” de la conservación tradicional ha resultado difícil de eliminar. Para muchos pueblos indígenas y comunidades locales, la conservación sigue siendo una práctica excluyente, que enfrenta a las personas con la naturaleza.

Un componente principal de su nuevo plan para salvar la naturaleza es la meta 3, que exige la protección de al menos el 30% de la tierra y los océanos del planeta para el 2030. Este objetivo, a menudo denominado 30×30, representa un compromiso para detener la pérdida de biodiversidad y transformar la relación de la humanidad con la naturaleza. Pero décadas de aprendizaje en el campo de la conservación, demuestran que dicho plan fracasará a menos que se haga hincapié en la primacía de los derechos humanos y se reconozca la importancia de los pueblos indígenas y las comunidades locales para el éxito de la conservación.

Pedimos a los líderes de todos los países y a sus representantes en la COP15 que eviten la inminente catástrofe de la biodiversidad garantizando que el compromiso 30×30 se aplique con el pleno consentimiento previo e informado, la participación y el liderazgo de los pueblos indígenas y las comunidades locales.

En concreto:

- Les pedimos que hagan más por la gente y el planeta, reconociendo que las estrategias de conservación y gestión ambiental deben ir más allá del 30% de la tierra y océanos protegidos y apoyar un enfoque de gestión del 100%, abordando los factores subyacentes de la degradación de los recursos y la pérdida de biodiversidad que también afectan al otro 70%.

- Les pedimos que en el objetivo número 3, garanticen y hagan referencia explícita a los derechos y a la tenencia de los pescadores a pequeña escala, de los pequeños agricultores, de los pueblos indígenas y de las comunidades locales. Para lograr esto, proponemos que lleven a cabo el “reconocimiento y la protección de los títulos, la tenencia, el acceso y los derechos a los recursos de los pueblos indígenas, las comunidades locales y los consumidores tradicionales de los recursos de la tierra y el océano, y que den prioridad a los sistemas de gobernanza y gestión dirigidos localmente o en colaboración”.

- Le pedimos que reconozcan que el consentimiento libre, previo e informado significa respetar los derechos de las comunidades y los pueblos indígenas a no participar en el proceso 30×30 y a no tener sus territorios designados como medidas de conservación o áreas protegidas.

- Le pedimos que aumenten drásticamente el apoyo financiero directo a los pueblos indígenas y a las comunidades locales en pro de la conservación, reconociendo que a pesar de sus contribuciones enormemente valiosas a la conservación y a la gestión medioambiental, sólo reciben una fracción de la financiación disponible.

Estas acciones contribuirán en gran medida a garantizar que el plan 30×30 sea algo más que una simple aspiración. Les instamos a ustedes, nuestros dirigentes, a adoptarlas y aplicarlas sin demora. La coexistencia entre las personas y la naturaleza es totalmente posible, pero sólo puede lograrse a gran escala con el pleno compromiso de quienes más dependen de la naturaleza: las personas históricamente marginadas que menos han contribuido a la crisis de la biodiversidad. Esta estrategia es clave para asegurar un futuro para toda la vida en la Tierra.

Atentamente,