Being an exhausted mother of 10 children by your early thirties is not unusual in rural Madagascar, but a movement is now underway to try and provide women with a contraceptive choice.

“I often get women in the clinic who have had eight or more children and are desperate to stop,” said nurse Rebecca Hill, who has been running a family planning clinic in Andavadoaka, a remote village in southwest Madagascar, for the past six months. “They are all too pleased to have a break, and family planning can allow that to happen. But there is a huge unmet need for these facilities here, and that needs to change.”

Madagascar, an island renowned for its unique biodiversity, is struggling to balance the demands of conservation with the needs of a rapidly growing population that has doubled in the last 25 years, reaching 19.6 million in 2007, according to UN figures. It is expected to hit 43.5 million by 2050.

Family planning initiatives in the cities have met with some success, but there is still a significant lack of contraceptive services in rural areas. “Reaching isolated communities is the real issue,” Andre Damiba, country director for Marie Stopes International (MSI), a reproductive health agency, told IRIN.

According to the government, in some parts of the country 70 percent of 16-year-old girls have already given birth to their first child. In recognition of the problem, the Ministry of Health has taken the unusual step of changing its name to include family planning.

The government has also made family planning one of the eight pillars of the Madagascar Action Plan (MAP), an ambitious economic and social development strategy recently launched by President Marc Ravalomanana.

The MAP sets two ambitious goals for family planning: reducing the average size of the Malagasy family “to improve the wellbeing of each family member, the community and the nation”; and comprehensively meeting the demand for contraceptives and family planning. It plans to do this by making contraceptives more widely available, providing educational programmes and reducing unwanted teenage pregnancies.

But the impact of the government’s efforts is yet to be felt in the remote villages of southwest Madagascar. Here, isolated coastal communities – among the poorest in the country – depend on dwindling marine resources that are under direct pressure from population growth in the villages, and health care and family planning services are extremely limited.

“A woman in the village of Andavadoaka who wanted to access contraceptive services faced a 50km journey on foot to Morombe, the nearest town, or would have to pay for passage on a passing ship,” explained Dr Vikram Mohan, founder of the clinic in Andavadoaka. “In cities there are good contraceptive services available; in remote areas like ours most organisations can’t offer a service.”

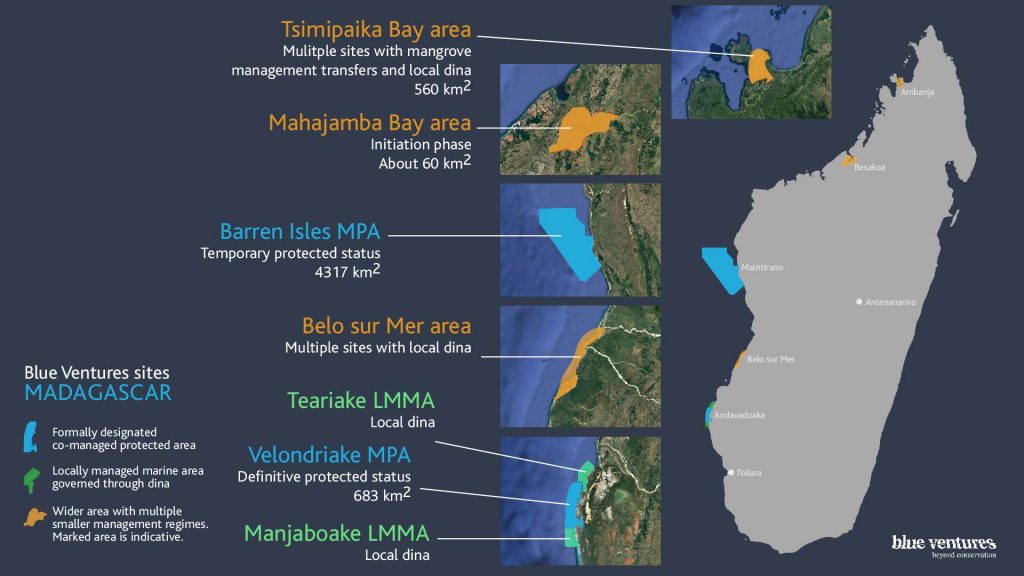

The Andavadoaka clinic is funded by a British charity, Blue Ventures Conservation (BVC). The link between population growth, the lack of family planning facilities and the increasing pressure on fragile natural resources prompted the organisation to establish the small clinic.

“The work being done by BVC to enable coastal communities to manage their resources sustainably ran the risk of being undermined by the mushrooming population of the community,” said Mohan. “In addition, an awareness of sexually transmissible infections and a willingness to take precautions was low.”

A recent UNAIDS survey in Madagascar found that only 12 percent of young men aged between 15 and 24 used a condom the last time they had sex with a casual partner. For women, the figure stood at 5 percent.

Empowering women

Damiba believes that intensive awareness raising campaign are needed, especially in rural areas where conservative traditions prevail. “It is only through the sensibilisation of communities that we can get behavioural change,” he explained. “As long as people’s behaviour doesn’t change there is no way of reaching the goals laid out by the government in the Madagascar Action Plan.”

For this reason, family planning is about more than just promoting the use of contraception; it is also about empowering women to make fundamental decisions that affect their health and lives. “Society here still lacks some understanding of what women’s rights are,” said Damiba. “We are raising awareness not just about women’s rights, but about their economic and social interests and about how they can take control of their lives.”

The women are learning fast. “Family planning is good for us,” said Veleriny, a member of the Andavadoaka women’s association. “It allows us to control when we give birth. Here some women become pregnant every year.”

The government uses the media to promote contraception, and international partners have become more active. “Access to family planning facilities is improving,” Lalah Rimboloson, deputy director of US-based Population Services International (PSI) in Madagascar, told IRIN. “Between 2004 and 2006 we saw a significant increase in the use of family planning. The government is encouraging organisations like PSI to increase their work.”

But national statistics do not always reflect the situation in remote areas. In 2007 the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) estimated the national fertility rate was 4.94 children per family. At the Andavadoaka clinic, nurse Hill estimates that in the remote coastal villages of the southwest it is as much as 8 to 12 children per family.

“We must have services made available permanently to those people who need them,” urged Damiba. “Services must be permanent, not just available once in a while,” otherwise real progress risks being limited to urban areas.

But the ambitious goals will be hard to meet. “I think that the targets of the MAP are reachable,” said Rimboloson, “but not with the government’s efforts alone; it has to be with all partners involved in family planning in Madagascar.”

Damiba agreed. “Even a small impact in a remote community can have a ripple effect in terms of helping to spread understanding and raise awareness of the issue. Everything counts. Family planning is really needed here.”