Original story published on Reuters on 14 November 2008, by Ed Harris.

ANDAVADOAKA, Madagascar, Nov 14 – Wading through the emerald green water with sharp eyes and a spear, Toline, 22, is hunting octopus in the baking midday sun.

ANDAVADOAKA, Madagascar, Nov 14 – Wading through the emerald green water with sharp eyes and a spear, Toline, 22, is hunting octopus in the baking midday sun.

“I started when I was young … on the back of my mother,” she told Reuters, dodging the treacherous spines of sea urchins.

For Toline’s fishing community on the southwest coast of Madagascar, octopus is of critical economic immportance, prompting village leaders to take innovative conservation measures that have won them global awards but also made them a test case for other fishing villages under pressure.

Mushrooming populations and commercial fishing are pressing the fishermen of Andavadoaka, known as the Vezo people, to catch more than a sustainable limit to maintain the area’s unique marine environnment of coral reefs, mangroves and sea grass beds.

“Yes, life has become difficult,” said one fisherwoman, Dorothe, 49, recalling the days when octopus were easier to find.

The Vezo used to catch just enough to feed their families, bartering for rice and vegetables with the inland farmers.

But since 2003, they have become part of an elaborate supply chain, selling their catch to traders who refrigerate and transport the goods, mostly octopus, for sale to Europe.

Chan Jaco, director general of processing company Copefrito, said Madagascar exports 1,200 tonnes of octopus a year of which about 800 tonnes come from the Toliara region in the southwest.

“And all of that comes from traditional fishing,” he said.

But while the fishing remains the same, the commercialisation has shifted local economies from barter to a cash-based competitive market, a fact lamented by local leaders.

“Everybody is now competing to buy a telly,” said Roger Samba, a local leader, who has been at the forefront of efforts to converve the village’s fragile marine ecosystem. “People are racing to fish, even fishing three times (in a day).”

With families of up to 17 children and an estimated 50 percent of the population under 14 years old, the Vezo population is growing rapidly, placing extra pressure on resources.

“That’s why lots of young Vezo women go to the bars to dance, look for a young man, to prostitute themselves,” he told Reuters. But the Vezo are facing up to their problems.

Samba heads an association covering 23 villages and 6,500 people which in 2004 outlined an area of about 800 square kms of shore and sea, forbidding the use of poison or mosquito nets to fish and placing temporary bans on fishing.

Octopus lay thousands of eggs if given the chance and anecdotal evidence showed clearly that their populations were bouncing back after the Vezo’s self-imposed bans took effect.

The World Wildlife Fund in October this year awarded Samba the 2008 Getty Prize for conversation leadership.

The Vezo are also looking to farm sea cucumbers, boneless and uncharming animals that fetch high prices on Asian markets.

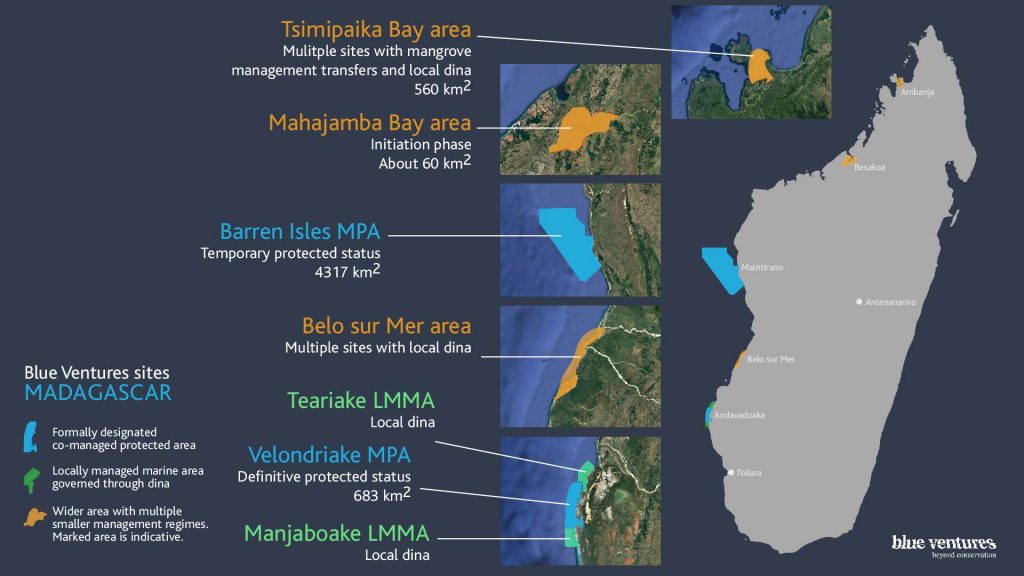

Dr Garth Cripps, project coordinator for Blue Ventures, a British conservation organisation in the area, said the ecosystem was at a crucial stage with Spanish and Asian trawlers reported fishing inside Madagascar’s territorial waters, and private companies introducing new techniques to increase local catches.

“It’s just, just surviving,” he said.

Samba sees education as vital to the Vezo’s survival, to open up other opportunities to earn money, perhaps as tourist guides for travellers who could pay for permits to go scuba diving.

But Cripps cautioned that if handled badly, tourism could be a disaster, upsetting the local environment with construction or fostering sex tourism as found down the coast.

“Do we want to build hotels where fishermen … become toilet cleaners and serve food to rich westerners?” he said.

“I don’t think the Vezo want that, but such is the dynamics of the population and the world today, they are going to have to face an influx of outside money and people.”