The last decade has seen a groundswell of community engagement in marine conservation across the Indian Ocean, yet few studies have documented the factors that have enabled effective conservation within these local initiatives. New research published this week draws together lessons from Madagascar’s first locally managed marine area (LMMA), generating valuable insights that can be used by managers around the world.

This study, published in the journal Conservation Science and Practice, synthesises lessons learned over the last fifteen years from the Velondriake LMMA in southwest Madagascar − the country’s longest standing community led marine conservation initiative. Velondriake’s model has since been replicated by communities along over 18% of the country’s inshore seabed, leading to the creation of a network of LMMAs sharing and learning best practices.

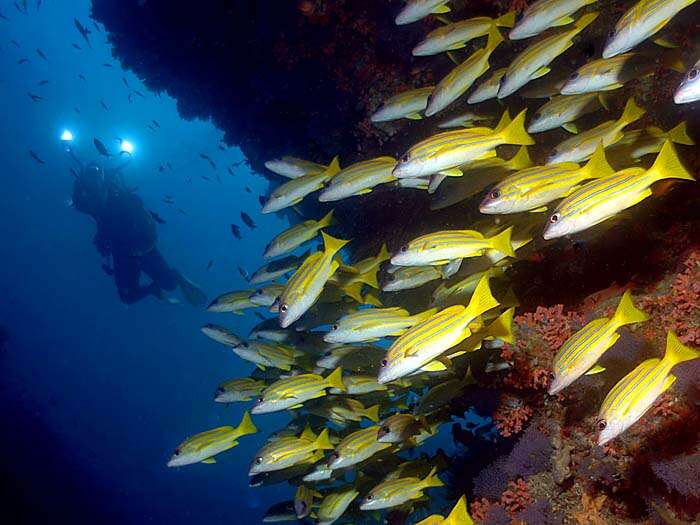

The Velondriake LMMA is located on the biodiverse southwest coast of Madagascar, where the population, primarily traditional Vezo fishers, is heavily dependent on the ocean’s resources for their subsistence.

Despite LMMAs being a widely used mechanism to ensure that small-scale fishing communities are at the centre of marine conservation efforts, there has been limited published understanding of the factors which make this approach effective. What’s more, the information we do have tends to be generated through quantitative scientific analyses, so it misses out on a valuable potential source of information − the insights and experiences of conservation practitioners themselves. The new research helps plug that gap by identifying the elements which have underpinned Madagascar’s LMMA success story, based on the ‘experiential data’ of Blue Ventures’ staff who have worked on Velondriake since the beginning.

Velondriake’s experience suggests that these locally led initiatives not only help to improve catches and restore threatened ecosystems but they also ensure that communities are empowered to steward the health and biodiversity of the marine ecosystems on which they rely.

In 2004, the community in the village of Andavadoaka, southwest Madagascar, closed a small area of its octopus fishing grounds for seven months with Blue Ventures’ support. The fishery closure successfully increased octopus catches, spurring neighbouring villages to replicate the model. These villages then came together to establish broader regional conservation and fisheries objectives, enshrined in customary law known as dina. Several years later these plans were formalised with the creation of a nationally recognised Marine Protected Area, known as Velondriake (which means “to live with the sea”). Velondriake’s management arrangement involves the Government, representatives of each of Velondriake’s 36 communities, and Blue Ventures.

Velondriake’s co-management approach, in which local communities receive sustained, long-term technical and financial support from a locally based NGO partner − in this case Blue Ventures − has been instrumental to the LMMA’s success.

The LMMA has been supported by a diversified funding model, drawing support from a range of donors as well as local revenues from alternative livelihood activities introduced by Blue Ventures, including seaweed farming, beekeeping, community-based tourism and blue carbon.

Velondriake’s use of a combination of scientific monitoring and traditional ecological knowledge to agree on zoning its various marine reserves has been instrumental to building community support for management, with decision-making in the hands of the local management association, not Blue Ventures. Velondriake’s 340 square kilometre management area encompasses seven permanent marine reserves protecting critical coral reefs and mangroves.

This new research sheds light on the process of co-managing Madagascar’s first LMMA through the experience of practitioners and community members to build on recent studies that demonstrate how these locally led areas can lead to ecological recovery and can deliver a benefit to fisheries.

While the Velondriake LMMA has been a partial success, the paper also identifies a number of challenges that still need to be overcome. Nevertheless, the lessons generated in the research will provide a valuable resource that will help conservation practitioners more effectively support the local managers of natural resources not just in Madagascar, but around the world.

Read the full paper in Conservation Science and Practice