This article was first published as a commentary on Mongabay on April 22nd 2020

Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on vulnerable communities in the Global South go far beyond the looming public health emergency. The broader economic and environmental ramifications are of profound importance to biodiversity conservation. How the conservation movement responds will determine our relevance and credibility in the eyes of many communities who depend on nature for their survival.

The coronavirus pandemic will disproportionately affect the poor. And for those who face the brunt of other global crises, Covid-19 is yet another tragedy. Isolated rural communities struggling with biodiversity loss already have the odds stacked against them. This new emergency exposes and intensifies the horrors of poverty and environmental collapse, and provides a forewarning of the kinds of social and economic shocks that will come with climate breakdown. Already tropical cyclones that would previously have captured headlines are going unheard amidst the pandemic’s global upheaval.

For two decades my organization has worked alongside coastal communities and partner organizations to rebuild tropical fisheries in low income countries and emerging economies. We have navigated turbulent times before, from catastrophic storms and infectious disease outbreaks to prolonged political unrest and conflict, but this crisis is testing our preparedness and ability as never before.

Everywhere we work we are seeing fisheries and seafood markets in turmoil. The supply chains at the foundation of most coastal economies are disrupted and fragmented by restrictions on the movement of people and goods. Tourism − also an economic lifeline for millions − has stopped dead. Disruption on this scale was unthinkable just weeks ago.

Communities who depend on these livelihoods face devastating losses of income, compounded by social isolation and obstructions to the supply of essentials, including food and medicines. Few poor coastal communities have any economic buffer or social support to ride out this storm. Women − who account for over one third of the world’s 60 million small-scale fishers, with still more living from fish processing and trading − will be particularly hard hit.

Coastal fishing villages in low income countries tend to be crowded, with many single-room houses packed tightly together. Houses typically lack running water and toilets. Water must be collected daily from communal wells. Under these conditions, social distancing can be impossible. We often work in contexts where there are simply no hospitals, let alone the medicines and PPE to save lives from the coronavirus. Millions live precariously with no social safety net and rely on fishing to make ends meet. In this perilous situation disruption to livelihoods intensifies communities’ dependence on natural resources to make ends meet, and brings new urgency to our mission.

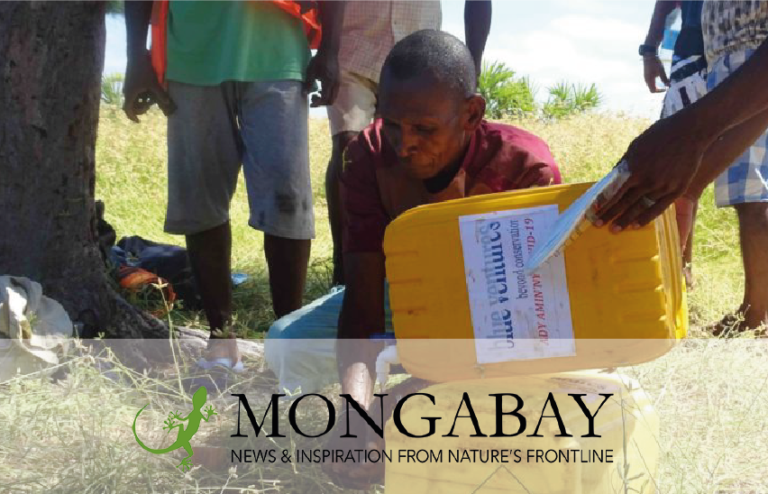

Our programs focus relentlessly on helping people live more sustainably with the ocean, and to overcome external shocks and pressures. We do this through practical efforts to improve catches, by diversifying livelihoods to reduce reliance on fishing, and by providing access to basic services such as community healthcare. With field teams living and working alongside under-served communities throughout the coastal tropics, we’re in a front line position to respond to this new challenge. Along with our partners, we are mobilizing around the world to help buttress locally led conservation efforts against the current crisis, safeguarding food security and livelihoods for coastal populations in this turbulent time.

We’re pooling resources with specialist organizations and government agencies to reach the most remote coastal communities with relief programs. We’re repurposing our logistics, boats, vehicles and teams wherever we can to help local government and community structures prepare for and combat the pandemic. We’re gathering and sharing information between communities and partners to ensure that the voices and needs of marginalized populations do not go unheard. And we’re ensuring our local partners have access to information and resources to help them shape their own responses to protect fisheries and livelihoods.

Beyond our work on the water, our community health teams have pivoted their operations to deliver a coordinated response to reduce community transmission of the virus, mobilize communities and partners to support the most vulnerable and help strengthen the existing health care systems so that they can cope with the pandemic, while maintaining essential health services. This sort of public health response is on a different scale to anything we’ve attempted before, aiming to reach nearly 400,000 people in Madagascar alone.

These efforts face the ultimate scrutiny from communities who count on their success, and to whom we are accountable. So we’re learning quickly − if more slowly than we would like − which approaches truly add value when they’re needed most. This reckoning is forcing us to make big decisions often in the face of huge uncertainty. Inevitably the experience is painful. Like so many organizations ours is being shaken by the immense strategic, financial and operational repercussions. Yet as we chart our course through the most rapid, momentous and far-reaching transition in human behavior that the world has ever known, we’re seeing new opportunities to refine our approaches. Our teams are being guided by our core values and “listen, plan, do, review, adapt, share” learning cycle to respond quickly, listening to communities and working holistically. Whatever the other side of this crisis looks like, we will be more attuned to local needs, and better informed to help communities navigate future climate shocks or market breakdowns.

Beyond our own efforts, our sector’s collective response to this pandemic will shape and sharpen the conservation movement that emerges from this crisis. Adaptations borne of today’s turmoil offer glimpses of a reformed conservation movement. We can only hope it will be better equipped to deliver value to communities and to weather the shocks of the future in pursuit of our collective conservation mission. We will learn anew the critical importance of redressing the imbalance of resources between north and south, and between bureaucracy and field delivery. And as distant offices struggle to mobilize international experts we will see the imperative of investment in the grassroots infrastructure and local leadership that are so fundamental to durable conservation. On the other side of the pandemic, we will have a precious opportunity to rejuvenate the outdated global apparatus of conservation, pivoting our sector towards the lower carbon efficiency that the future demands.

For conservationists working at the interface of poverty and environmental degradation, the coronavirus tragedy underscores why we must take urgent action to support those dependent on biodiversity for their survival. The impact we make today could be the most important work of our lives. Never has our mission mattered more.

We’re appealing for your support – please join us