On 22nd February, we received confirmation that commercial shrimp trawlers would cease fishing the sensitive corridor between the Barren Isles Marine Protected Area and the shores of the Melaky region in western Madagascar. This is the first step in the implementation of a new fisheries management plan that will ultimately benefit traditional fishers, the local marine environment and help reduce pressure on declining shrimp stocks.

Ever since President Tsiranana retracted the law protecting the nearshore zone for the exclusive use of traditional fishers in 1971, relations between the fishers and shrimp trawlers have been strained. These two groups are competing for dwindling resources on vastly different scales, with much higher stakes involved for the traditional fishers who depend on their catch for their food security and livelihoods. To make matters worse, a traditional fisher who sets his nets in nearshore areas runs the risk of having them destroyed by passing trawlers – a mighty blow for a subsistence fisherman with no other means of income. Historically, they have had no official platform on which to negotiate a solution, so their calls for compensation and feelings of anger and helplessness remained unresolved.

The Melaky region remains very remote and is hampered by ever-worsening transport links. Thanks in part to its relative isolation, its marine ecosystems are remarkable for their diversity and abundance, and harbour some of the western Indian Ocean’s healthiest coral reefs. However, a holistic management plan was long overdue, as these productive ecosystems have been subject to increasing open-access exploitation by many and various users, both legal and illegal.

After years of negotiations, November 2016 saw the signing into law of the Melaky Fisheries Management Plan – the first to be made on a regional scale in Madagascar. This plan represents the combined efforts of numerous stakeholders, principally traditional fishers, the government and industrial fishing companies, all working towards a shared vision – a healthy, productive fishery that benefits all. Finally, a dialogue has begun between these very different groups and now fishers have a real chance to make their voices heard.

Fishing is particularly important for the local people: the Melaky region has limited infrastructure and few alternative employment opportunities, so the majority of its coastal population continues to depend on marine resources for their livelihood. For example, the Barren Isles archipelago – a group of nine coral-sand islands with no fresh water – is exceptionally rich in marine life, and supports the livelihoods of more than 4,000 traditional small-scale fishers. Although red with silt, the region’s nearshore waters are also an important source of food for local fishers, including shrimp and catfish.

As well as the local fishers, every austral spring brings waves of migrant fishers from southwest Madagascar in their traditional pirogues, ready to fish the region’s plentiful waters for up to eight months. But with the increasing degradation of the rest of western Madagascar’s fisheries over the last few decades, due to intensive and destructive fishing practices and inadequate governance, the number of migrant fishers grows yearly. And every year, fewer of them return to their distant homes, preferring to stay closer to one of the country’s last reliable fishing grounds.

There is evidence the fishery is declining: according to the Ministry for Aquatic Resources and Fisheries (MRHP), shrimp trawlers (the Melaky’s dominant commercial fishers) now extract a total of around 3,400 tonnes of shrimp a year, 59% less than they did in 2001. The region’s precious resources are also under pressure from illegal and unregulated fishing vessels and sea cucumber harvesters using scuba gear, mining interests, and destructive fishing practices. The effects of intensifying open access exploitation were threatening the very survival of one the western Indian Ocean’s last hotspots of marine biodiversity.

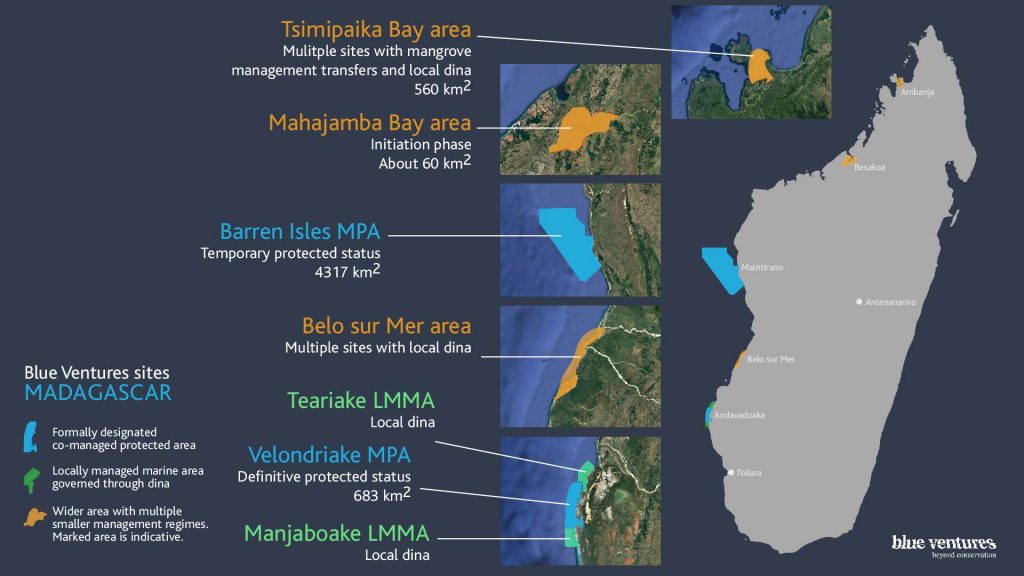

There is now a ray of hope: after seven years of hard work, Blue Ventures and partners successfully won temporary protected status for the Barren Isles archipelago in 2014, towards being definitively gazetted as a sustainable use marine protected area (known as a locally managed marine area – LMMA) in the near future. Covering 4,300 km2, it is the western Indian Ocean’s largest marine protected area, from which all industrial fishing has been excluded and small-scale fishing will now be regulated with the use of licenses and gear restrictions. Building upon that great milestone, the Melaky Fisheries Management Plan was negotiated and ratified just two years later, thanks to the sustained efforts of the MRHP with support from Blue Ventures.

Upon the launch of the plan last year, Francois Gilbert, the Minister of Fisheries, said:

“local populations must be included among those who will benefit from the fruits of the exploitation of marine resources. Indeed, the resources belong to them first.”

The national shrimp trawling association GAPCM’s recent decision to cease trawling in the ‘sensitive corridor’ over the 2017 fishing season is a direct result of this new plan being put into action. We are particularly pleased to have reached such an encouraging agreement with the shrimp trawling industry, and we hope that together we can achieve better and more equitable fisheries practice.

However, this recent win is just the beginning. The closure has been put in place on a trial basis, and will need to be renegotiated for the 2018 fishing season. Over the coming months, our main challenge will be to gather evidence of the impact of the closure on the fishery. More broadly, the management plan involves a wide array of measures that must be implemented by local associations and regional institutions, and ensuring their success will require further capacity building. As the principal technical advisor in the region, Blue Ventures will continue to support this process every step of the way.

Overall, we are feeling optimistic about the future for the region’s traditional fishers. In the past, such widely different and dispersed stakeholders had no way to exchange ideas and grievances, and the very concept of building a more sustainable fishery appeared to be a pipe dream. But this recent positive result shows that a collaborative management approach can deliver real change for a vulnerable community.

We would like to thank our funders for their support, including: the GEF through UNEP under the Dugong and Seagrass Project, the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund and the Darwin Initiative through UK Government funding.

We would like to thank our funders for their support, including: the GEF through UNEP under the Dugong and Seagrass Project, the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund and the Darwin Initiative through UK Government funding.